David Emerick analyzes the shifting role of the starting pitcher (SP) in fantasy baseball and how it may be increasing the draft value of elite starters in 2019.

After San Francisco Giants’ president Farhan Zaidi announced that the team might use an opener this season, Madison Bumgarner messaged Bruce Bochy: “If you use an opener in my game I’m walking right out of the ballpark.”

In addition to giving us the most Madison Bumgarner quote of all time, the news prompted me to reconsider for the umpteenth time if elite starting pitchers are currently undervalued in fantasy baseball. Given baseball’s adoption of the opener, it seems possible that the 34-year-old Max Scherzer is the best first-round value outside of Mike Trout and Mookie Betts.

It used to be the case that waiting on a starter was advisable in the early rounds but the dwindling amount of true aces in baseball has led to eight SP finding their way into the top 30 selections based on current ADP. Let's examine whether opening with a strong starting pitcher is, in fact, the best move.

Be sure to check all of our fantasy baseball lineup tools and resources:- Fantasy baseball trade analyzer

- BvP matchups data (Batter vs. Pitcher)

- PvB matchups data (Pitcher vs. Batter)

- Who should I start? Fantasy baseball comparisons

- Daily MLB starting lineups

- Fantasy baseball closer depth charts

- Fantasy Baseball live scoreboard

- Fantasy baseball injury reports

The Changing Role of Starters

The opener is only the most recent development in the shrinking role of starters. While 260 innings a season is long gone, baseball may be approaching the point where even 200 innings becomes an exceptional performance. In the last decade, the game has seen a drop in complete games, innings per start, and the number of quality starts.

Although the opener came to public consciousness relatively late last season, six organizations used the strategy by the end of the season. Given its success for competitive teams, it’s easy to imagine more clubs will use it to protect young, old, and borderline pitchers.

It seems likely the Giants will also use the strategy (just not with Bumgarner). That makes sense. If a club doesn’t have to use an extra pitcher to start a game for their ace, they probably won’t. Even though he claimed to be joking, it doesn’t look like he was in any real danger of the Giants confiscating his God-given right to the opening pitch. Outside of staff aces like MadBum, many starters could benefit from the strategy, and that expansion could accentuate the value of top-tier starting pitchers.

Furthermore, as teams continue to pull starters earlier and earlier in games, it seems likely to yield fewer wins for starters. Since 2014, teams have reduced starter usage in large part because pitchers perform worse on the third time through the batting order. Health concerns, advanced analytics, and shifting bullpen strategies have curtailed the number of starters going into the seventh inning. Now, the opener adds a bookend at the start of the game as well as the sixth inning when leadoff hitters often come to the plate for the third time. If there are fewer wins available for starters and absolutely fewer quality starts, then elite starters, who pitch further into games, earn more quality starts, and earn a greater percentage of wins should be worth more this season than they have in the past. Is this true?

However, the initial data didn’t offer simple, actionable clarity.

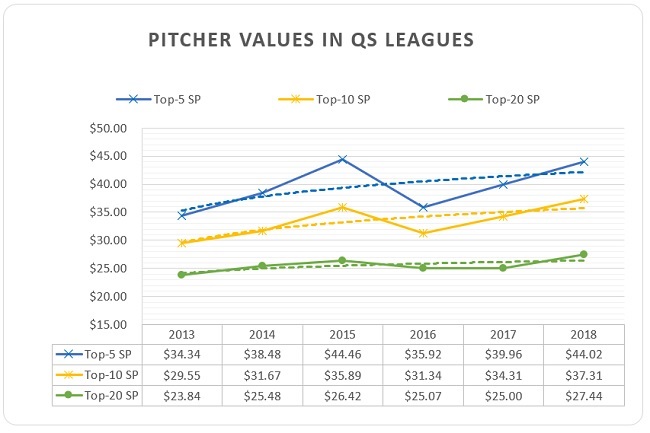

For calculating value, I used a straightforward 12-team setup for 5x5 leagues. I made two sets of leagues and tables, one using wins and one using quality starts. Rosters used standard positions with a corner infield spot, middle infield spot, and a utility spot, five starters, three relievers, and a 70/30 offense/pitching split for a $260 league. Initially, I examined the top 20 starters in both formats from 2013 to 2018, which yielded these results:

| Year | QS% | IPS | CG | Top-20 SP Value (W Leagues) |

Top-20 SP Value (QS Leagues) |

| 2013 | 53 | 5.9 | 124 | $21.25 | $23.84 |

| 2014 | 54 | 6.0 | 118 | $20.51 | $25.48 |

| 2015 | 50 | 5.8 | 104 | $23.25 | $26.42 |

| 2016 | 47 | 5.6 | 83 | $20.66 | $25.07 |

| 2017 | 44 | 5.5 | 59 | $21.74 | $25.00 |

| 2018 | 41 | 5.4 | 42 | $22.25 | $27.44 |

The first thing I noticed was how noisy the data was. While there appeared to be real patterns in the raw data on pitcher performance and player value, there were enough anomalies combined with the small samples that it was a challenge to find coherent patterns. A quick look at the Top-20 SP Values for both league types shows that even though starters are being pulled earlier, the value of top-20 starter hasn’t changed much in wins leagues despite earning a greater percentage of the available quality starts. Given the modest correlation between the two stats, it’s surprising that the values aren’t closer.

Another item which caught my attention was the value of the top three pitchers in 2015. That year is a bit anomalous because Jake Arrieta (8.3 bWAR, 7.3 fWAR), Zack Greinke (9.1 bWAR, 5.8 fWAR), and Clayton Kershaw (7.5 bWAR, 8.5 fWAR) all produced seasons of outstanding fantasy value. That season alone complicates the charts because the three data points significantly impact the overall trends for both wins leagues and QS leagues.

Indeed, Kershaw nearly skews (or even distorts) the 2013 to 2015 data by himself. At that time, he was the best pitcher in baseball and should have been going in the top three picks in nearly all formats. While Kershaw was sometimes selected that early, it was less common than it should have been. Frequently, he was slipping into the second half of the first round.

In 2013, pitchers in Quality Starts leagues (QS from here forward) were similarly valuable to pitchers in wins leagues, but that has changed substantially as the number of quality starts has declined. As a result, elite pitchers, who generate quality starts 80 to 90% of the time have higher value, and their value in QS leagues has migrated away from their value in wins leagues.

Elite Pitcher Value in QS Leagues

The table above shows that top-20 starters in QS leagues have consistently increased in value over the last six seasons. As I mentioned earlier, 2015 becomes an odd example, but even in that case, if we use head-to-head comparison rather than averaging the five pitchers, the 2018 group outperforms the 2015 group.

| 2015 | 2018 | |

| 1 | 50.4 | 51.6* |

| 2 | 50.2* | 45.8 |

| 3 | 50.1* | 43.5 |

| 4 | 36 | 39.6* |

| 5 | 35.1 | 39.6* |

I’m not sure yet if we should count those fourth and fifth starters as elite. In most seasons, there is a significant drop off between SP3 to SP5. For now, we’ll leave that as an issue for Part 2 of this series.

Fortunately, the charts and tables below do clarify that the increase in value has not been evenly distributed across all starters. In QS leagues, starters, in general, have not become more valuable, only top-tier starters. The two charts below show that the five best pitchers in each league have become increasingly more valuable. Again, the 2015 season make those trends a bit more complex.

Despite that historic combination of performances from Arrieta, Greinke, and Kershaw, a top-20 starter in 2018 was still worth a dollar more than in 2015 and more $2.44 more than 2017. There is no other single-year jump that significant, and the most substantial two-year change (2013 to 2015) is only slightly larger at $2.58.

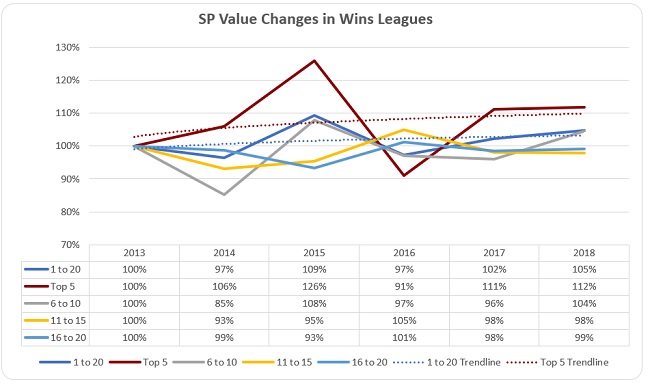

Elite Pitcher Value in Wins Leagues

For wins, the data is more complex and frustrating than quality starts. The chart and table below illustrate how top-20 starter values have changed. Initially glancing through the numbers, it’s not actually clear that elite starters are worth more than they have been. The top-five pitchers in 2018 look like a similar value to the top-five pitchers from 2017, which is pretty similar to 2014. Meanwhile, 2015 is measurably higher than the five other seasons. There’s a general trendline upward, but given the rest of the data, the pattern is uncompelling.

I spent some time looking for reasons that pitchers in QS leagues would have been more valuable while pitchers in wins leagues might not be. I never found a clear pattern, but as I was working, I spent some time looking at the values of each pitcher over the last six years. I’ll write more about that in Part 2, but it led me to track the relative values of each pitcher within the top 20. For example, the best pitcher in baseball was worth $42.60 in 2013, $40.20 in 2014, $45.30 in 2015, $30.40 in 2016, $40.30 in 2017, and $36.30 in 2018. Initially, it seemed as though pitcher values had not changed meaningfully in wins leagues despite the change in usage trends. Once I had tabulated the data though, it seemed like a pity not to graph it, which gave me this chart.

If you drink two beers, squint, and turn your head to the side, you might notice the same things I did. Or not. I’d had more than two beers when I noticed it. Since 2016, there is a general vectoring upward for the top-five pitchers, even allowing for the phenomenal talent of Clayton Kershaw. Likewise, the bottom 10 pitchers are increasingly compacted over the last four years. The compaction could be easily explained by standard deviation within the sampling distribution, but it prompted me to sort the pitchers into quartiles.

To be profoundly scientific about the data, the lines at the end of the chart (2018) are generally higher than the lines at the beginning of the chart (2013). It’s possible that might suggest that elite pitchers are worth more in wins leagues now. Or it could be a limitation of the data. Obviously, the top-five pitchers saw the greatest increase, and pitchers from 11 to 20 saw a modest decrease, but their value is probably best described as static.

Unlike QS leagues, it’s hard to argue that elite pitchers are clearly more valuable in wins leagues. They might be, but the data for wins leagues is more complex than the data for QS leagues.

There are a number of reasons why wins leagues might not shift similarly to QS leagues. As we know, wins are less correlated with pitcher performance than quality starts. Additionally, it’s possible that starters are better protected by teams who pull them earlier. If a team pulls a starter earlier and successfully protects a lead, that pitcher may be more likely to earn a win than he was in the past.

Likewise, an opener might very well improve a starter’s chance of winning because the opener makes it less likely the starter must face the top of the lineup for a third or fourth time. Additionally, the opener allows a starter to pitch later in the game when he is more likely to earn a win. Despite the modest correlation between wins and quality starts, it’s possible that the introduction of the opener makes the two stats less correlated across the league. Ostensibly though, that shouldn’t make the stats less correlated between elite starters who are unaffected by openers.

Conclusion

Current projections systems don’t appear to account for further adoption of the opener strategy, and it’s not clear if we’ve reached the inflection point for openers. To be fair, there’s no easy way to account for it. Since projections systems rely entirely on methodical approaches to the data, there is no systematic way to account for the opener that doesn’t rely on speculation.

In that spirit though, let’s speculate, but conservatively and in general terms. Six teams used the opener in 2018, so let us predict that six teams will use it again (even if it’s not the same six). Remember that most of those six teams attempted the strategy only at the end of the season. If those teams use it for the entire 2019 season, whatever effect the opener has on starting pitcher values will be compounded. If the opener becomes even more commonplace, elite starters may well become more valuable than even the best offensive players, and we may need to re-evaluate the 70/30 offensive/pitching split.

Regardless of speculation though, the data suggests we might be better off moving top-tier pitchers up in our draft rankings and inflate the values of top-tier starters more than we inflate the values of top-tier hitters. The effect is basically the same.

Right now, even the most aggressive prediction and value models that I’ve seen have applied inflation evenly between pitchers and hitters. Some apply early-round inflation to hitters more aggressively than pitchers. Given the data above, offensive-tilted or even-split inflation rates seem ill-advised at this point.

If the number expands, and a total of ten teams use the opener with their two worst starters this season, then 13% of the games are guaranteed not to yield a quality start. Furthermore, as teams continue to pull starters earlier and earlier in games, it seems likely, though not guaranteed to decrease the number of wins for starters. If there are fewer wins available for starters and absolutely fewer quality starts, then elite starters, who pitch further into games, earn more quality starts, and earn a greater ratio of wins should be worth more this season than they have in the past.

2019 should provide a clearer sense of how many starters are affected by the opener strategy. Hopefully, that will provide some clarity for how to better evaluate starting pitchers. For now, top-tier starters get a boost in value in QS leagues. That’s especially true for starters like and Scherzer who own exceptional QS rates. It’s less clear in wins leagues, but a minor adjustment seems advisable for owners looking to capitalize on a potential

In future articles, I’ll look at where elite starters come from (hint: it’s not the Arizona Fall League) and where elite pitchers such as Scherzer, Sale, and deGrom should be going in drafts.

RADIO

RADIO